Publications

Accessing U.S. Capital Markets

The Australian innovation economy is producing remarkable success stories, despite a relative dearth of investment. In fact, a recent study by Side Stage Ventures, Dealroom.co, and AWS Startups, has found that in the last 25 years, Australia has produced 1.22 unicorns for every $1 billion invested – the highest ratio globally and almost double the unicorn-to-dollar ratio in the United States or China. The Australian tech ecosystem is also an impressive growth story, growing at the second fastest rate in the world and almost catching up to the global leader, India. Furthermore, Australia’s proven track record of profitable exits is driving overseas investment – nearly 40% of early stage capital in Australia comes from abroad.

Statistics like these help increase U.S. investors’ interest in Australian companies and may make it easier to pitch them successfully. There are, however, certain considerations that can stop an investor from pulling the trigger and doing a deal. These considerations have nothing to do with the company’s products or services, growth potential, or management. Rather, they relate to the legal and regulatory considerations facing U.S. investors. This article will discuss four such considerations that every Australian company must take into account as it prepares to access U.S. capital markets.

Creating a U.S. Corporate Entity

In general, U.S. investors prefer to invest in U.S.-based entities. This preference is based on familiarity with the regulatory and legal regimens governing U.S. corporate entities, the undesirability of dealing with two different taxation systems, and the tax advantages that investing in U.S.-based companies provides.

Therefore, if an Australian company wants to access U.S. capital markets, it is advisable to set up a U.S. corporate structure. The following are the most common options companies evaluate based on their capital raising strategy and operational goals:

- Parent Structure: The Australian company becomes a wholly owned subsidiary of a newly formed U.S. parent. This is commonly achieved by having all existing shareholders exchange their shares in the Australian company for shares in the U.S. entity. This structure is particularly attractive to U.S. investors.

- Subsidiary Structure: The Australian company remains the parent, and forms a wholly owned U.S. subsidiary to conduct operations and raise capital in the U.S. While this structure may be suitable for operational reasons, it can be less appealing to U.S. investors unless they want to focus their investment into the U.S. portion of the business.

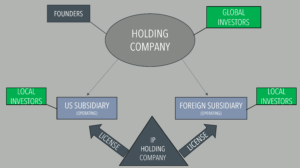

- Holding Company Model: In some cases, a global holding company is formed to own both U.S. and foreign subsidiaries. This model can be useful when IP ownership, licensing, or multi-jurisdictional investor pools are involved. The holding company is often incorporated in Delaware due to historical legal reasons, although sometimes global enterprises choose other jurisdictions (whether in or outside the U.S.) due to governance, tax or regulatory advantages.

- Affiliated Entity Licensing Structure: In certain cases (such as when the Australian company receives government grants that require it to remain the operating entity) two affiliated entities may exist: one in Australia and one in the U.S. These entities are tied together through a licensing agreement, allowing the U.S. entity to commercialize IP owned by the Australian company. If set up properly, this structure can preserve eligibility for local incentives while enabling U.S. fundraising and operations.

Financing Options

When raising capital, startups must carefully consider the structure of the financing round. The choice between debt and equity (and the instruments used) can significantly impact control, dilution, and investor alignment. Common financing instruments include:

- Equity Financing: Sale of common or preferred stock in exchange for ownership. Preferred stock often includes investor protections such as liquidation preferences and anti-dilution rights.

- Convertible Notes: Short-term debt that converts into equity, typically at a discount to the next priced round. These are popular for early-stage fundraising due to their simplicity and speed.

- SAFEs (Simple Agreements for Future Equity): Similar to convertible notes but without the debt component. SAFEs are widely used in seed rounds and offer flexibility for both founders and investors.

- Warrants: Rights to purchase stock at a fixed price in the future. Often used as a sweetener in financing rounds.

- Traditional Debt Financing: Loans that must be repaid with interest. May require collateral and impose covenants.

- Crowdfunding: Raising capital from a large pool of small investors, typically via online platforms. Regulation Crowdfunding allows eligible companies to offer securities to the public under certain conditions.

Regardless of the instrument chosen, companies must ensure compliance with both federal and state (“blue sky”) securities laws. While federal law (primarily governed by the Securities and Exchange Commission) sets the overarching framework for registration and exemptions (such as Regulation D), individual states may impose additional notice filing requirements, fees, and investor protections.

The Qualified Small Business Stock (QSBS) Tax Advantage

One of the biggest advantages for an investor in an early-stage U.S. company is the tax treatment of QSBS – which has gotten even more generous under the recently passed One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB). Holding QSBS can drastically lower the capital gains tax liability for startup founders and early investors – as much as a 100% exemption on federal capital gains taxes on up to 10X their original investment. Before the OBBB, the cap on the exemption was $10 million for investors who have held the QSBS for a minimum of 5 years. Under the OBBB, the exemption cap has been raised to $15 million, with partial exemptions of 50% or higher available to those holding the stock for at least 3 years. In addition, the gross assets cap for being considered a “small business” has been expanded from $50 million to $75 million. The QSBS is a highly significant incentive to invest in small U.S. businesses, and by setting up a U.S. entity, Australian companies can tap into the increased demand for investible businesses created by the QSBS tax advantage.

IP Footprint

Protecting a company’s IP is an expensive undertaking, and there is sometimes a tendency to obtain protection only in one’s home country. But a company’s IP is often its most important asset, and savvy investors want to see that it is protected in all key markets, if not globally. Otherwise, a company leaves itself open to being outflanked by competitors who practice its innovations in jurisdictions where the company had failed to apply for patent, trademark, or copyright protection.

Before pitching U.S. investors, it is crucial to conduct an inventory of the company’s IP rights and patch any significant deficiencies.

***

There is significant appetite among U.S. investors to provide capital for innovative businesses. If your company is considering raising capital in the United States, we can help. Reach out to either Katherine Rubino, Andrew Ritter, or Giuseppe Scaravilli to discuss how we can support your company’s strategic vision.